Chapter Two: IRELAND’S ANCIENT ALPHABET

Ogham is Ireland’s ancient linear script (alphabet) and form of communication

that starts with the Bronze Age Tuatha de Dannan and it continues in use after

the invasion by the Iron Age Milesians. It takes the form of linear strokes cut into

stone, carved onto natural materials such as wood and amber, or written down.

that starts with the Bronze Age Tuatha de Dannan and it continues in use after

the invasion by the Iron Age Milesians. It takes the form of linear strokes cut into

stone, carved onto natural materials such as wood and amber, or written down.

The earliest known Ogham is found on standing stones and in early and late medieval manuscripts. It must always be noted that the medieval scribes were under the instruction of the Church to absorb and suppress the indigenous traditions with policies of confusion and disinformation and to covertly encode the Church’s agenda into their handwritten books about Ireland’s history. This attitude of covertly encoding the Church’s agenda was also applied to old Gael Law / Fenechus (often mistakenly referred to as Brehon Laws) as the Church remodeled the natural law of the land to suit its own hierarchical control agenda. This imperial literary tradition that was imposed on our living cultural expression and practice was not written by the Celts, nor is it the history of the Celtic Gael.

But of course, in the imperial literary tradition, if it is written down then it must be true, but we all know today that this is simply not the case. The Sun does not rotate around the Earth for example, and Limbo, after centuries of contrary indoctrination is now merely ‘a theological speculation’. Ogham is often presented by modern scholars and enthusiasts as a tree alphabet, where every symbol of the Ogham alphabet represents a tree, however this is also not true. The tree connection refers to the form the symbols take - forked or branched lines and the way Ogham is to be read most often, from the base or root up. Medieval church scribes started this confusion and it was then further compounded by 18th and 19th century historians and Masons who evolved a tree calendar and zodiac based on the misrepresentation of Ogham as a tree alphabet. The oldest books we know about that feature Ogham ‘alphabets’ were written by scribes of the Catholic Church and were not edited by the indigenous people to be a true representation of an existing culture. These church written alphabets were clumsy contrivances designed to incorporate indigenous history into the Catholic narrative, and they demonstrate the intentions of the Church over the existing local traditions. These layers of obfuscation must be thoroughly investigated and removed in any search for the truth about the use of Ogham by the native population. A part of this book is dedicated to the undoing of the fake histories of Ogham by the Church and the subsequent misrepresentation of Ogham by those who created false tree calendars and zodiacs based upon false historical accounts.

The Origins of Ancient Ogham

Ogham is the ancient written ‘alphabet’ of the pre-Celts / Celts or indigenous peoples of Western Europe. It is claimed that in writings from the 7th century copied into a manuscript known as Auraicept na hÉces that Ogham was created by Ogma mac Elathen, brother to the Dagda and half-brother to Lugh, all three being Gods of the Tuatha de Danann, which dates Ogham’s creation to at least four thousand years ago. In Lebor Ogaim ("The Book of Ogams" 1390CE) we are told that Ogma is a man skilled in speech and poetry who invented Ogham as proof of his genius and to create a form of communication to keep learned men apart from rustics. Ogma was a great warrior and he was also King Nuada’s battle champion too.

Ogma was such a skilled poet and orator that he got nicknames such as ‘Honey-Mouth’ and ‘God of Eloquence’. In the same Lebor Ogaim, Ogma is called the father of the Ogham alphabet and in the same book we get lists showing over a hundred variations of Ogham. This is why this book is dedicated to Ogma. The most widely recognised and oldest Ogham script is found in the The Book of Ogams and is shown to have twenty distinct symbols called ‘Fews, Fidh or Feda’, the term ‘symbol’ will be used throughout this book. Five of these symbols make up a family called ‘Aicmí’. To this original twenty symbols an extra five additional symbols were added by the Church called ‘Forfeda’ making a total of 25 Feda / symbols. Because these Forfeda are not seen on standing stones but instead only appear in the Manuscript Tradition it is reasonable to assume that they are a later addition by the church.

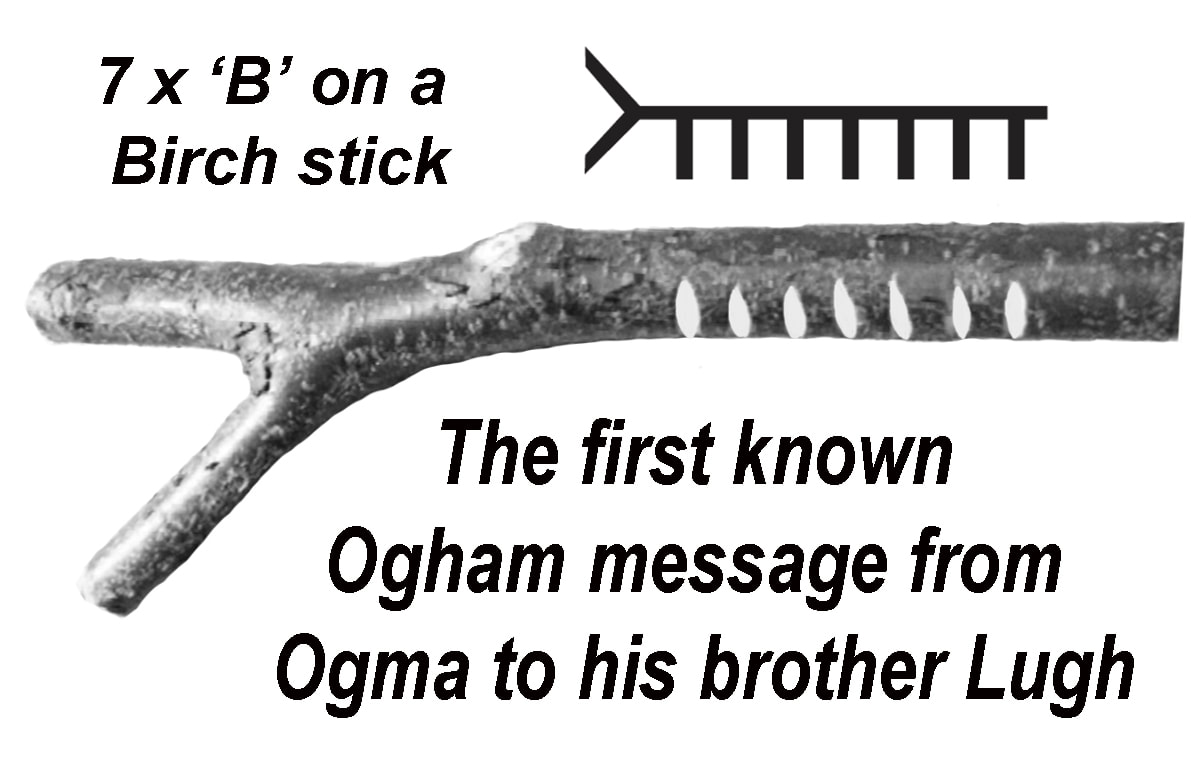

Ogham was written vertically from the feet / roots up, sometimes horizontal i.e. left to right and also from the top down. In Auraicept na hÉces, a 12th century collection of older manuscripts, we are told how to read Ogham: “Ogham is climbed (i.e. read) as a tree is climbed, i.e. treading on the root of the tree first with one’s right hand before and one’s left hand last. After that it is across it and against it and through it and around it.” In the Lebor Ogaim it is recorded that the first message written in Ogham was seven b's on a birch stick.

But of course, in the imperial literary tradition, if it is written down then it must be true, but we all know today that this is simply not the case. The Sun does not rotate around the Earth for example, and Limbo, after centuries of contrary indoctrination is now merely ‘a theological speculation’. Ogham is often presented by modern scholars and enthusiasts as a tree alphabet, where every symbol of the Ogham alphabet represents a tree, however this is also not true. The tree connection refers to the form the symbols take - forked or branched lines and the way Ogham is to be read most often, from the base or root up. Medieval church scribes started this confusion and it was then further compounded by 18th and 19th century historians and Masons who evolved a tree calendar and zodiac based on the misrepresentation of Ogham as a tree alphabet. The oldest books we know about that feature Ogham ‘alphabets’ were written by scribes of the Catholic Church and were not edited by the indigenous people to be a true representation of an existing culture. These church written alphabets were clumsy contrivances designed to incorporate indigenous history into the Catholic narrative, and they demonstrate the intentions of the Church over the existing local traditions. These layers of obfuscation must be thoroughly investigated and removed in any search for the truth about the use of Ogham by the native population. A part of this book is dedicated to the undoing of the fake histories of Ogham by the Church and the subsequent misrepresentation of Ogham by those who created false tree calendars and zodiacs based upon false historical accounts.

The Origins of Ancient Ogham

Ogham is the ancient written ‘alphabet’ of the pre-Celts / Celts or indigenous peoples of Western Europe. It is claimed that in writings from the 7th century copied into a manuscript known as Auraicept na hÉces that Ogham was created by Ogma mac Elathen, brother to the Dagda and half-brother to Lugh, all three being Gods of the Tuatha de Danann, which dates Ogham’s creation to at least four thousand years ago. In Lebor Ogaim ("The Book of Ogams" 1390CE) we are told that Ogma is a man skilled in speech and poetry who invented Ogham as proof of his genius and to create a form of communication to keep learned men apart from rustics. Ogma was a great warrior and he was also King Nuada’s battle champion too.

Ogma was such a skilled poet and orator that he got nicknames such as ‘Honey-Mouth’ and ‘God of Eloquence’. In the same Lebor Ogaim, Ogma is called the father of the Ogham alphabet and in the same book we get lists showing over a hundred variations of Ogham. This is why this book is dedicated to Ogma. The most widely recognised and oldest Ogham script is found in the The Book of Ogams and is shown to have twenty distinct symbols called ‘Fews, Fidh or Feda’, the term ‘symbol’ will be used throughout this book. Five of these symbols make up a family called ‘Aicmí’. To this original twenty symbols an extra five additional symbols were added by the Church called ‘Forfeda’ making a total of 25 Feda / symbols. Because these Forfeda are not seen on standing stones but instead only appear in the Manuscript Tradition it is reasonable to assume that they are a later addition by the church.

Ogham was written vertically from the feet / roots up, sometimes horizontal i.e. left to right and also from the top down. In Auraicept na hÉces, a 12th century collection of older manuscripts, we are told how to read Ogham: “Ogham is climbed (i.e. read) as a tree is climbed, i.e. treading on the root of the tree first with one’s right hand before and one’s left hand last. After that it is across it and against it and through it and around it.” In the Lebor Ogaim it is recorded that the first message written in Ogham was seven b's on a birch stick.

Plate 1: 7 x ‘b’ on a birch stick

Note that the accepted symbol for Birch is a ‘b’ or a single downwards half line from the central stem. These 7 ‘b’s are on a Birch stick (a ‘b’ itself) and that this may mean that there are 8 ‘b’s instead of 7. This first message in Ogham was sent by Ogma to his bother Lug as a warning, meaning; “Your wife will be carried away seven times to the Otherworld unless the Birch protects her.” We do not know how or why exactly it means that, or if this is just a creation of the Church scribes who wrote this down centuries later.

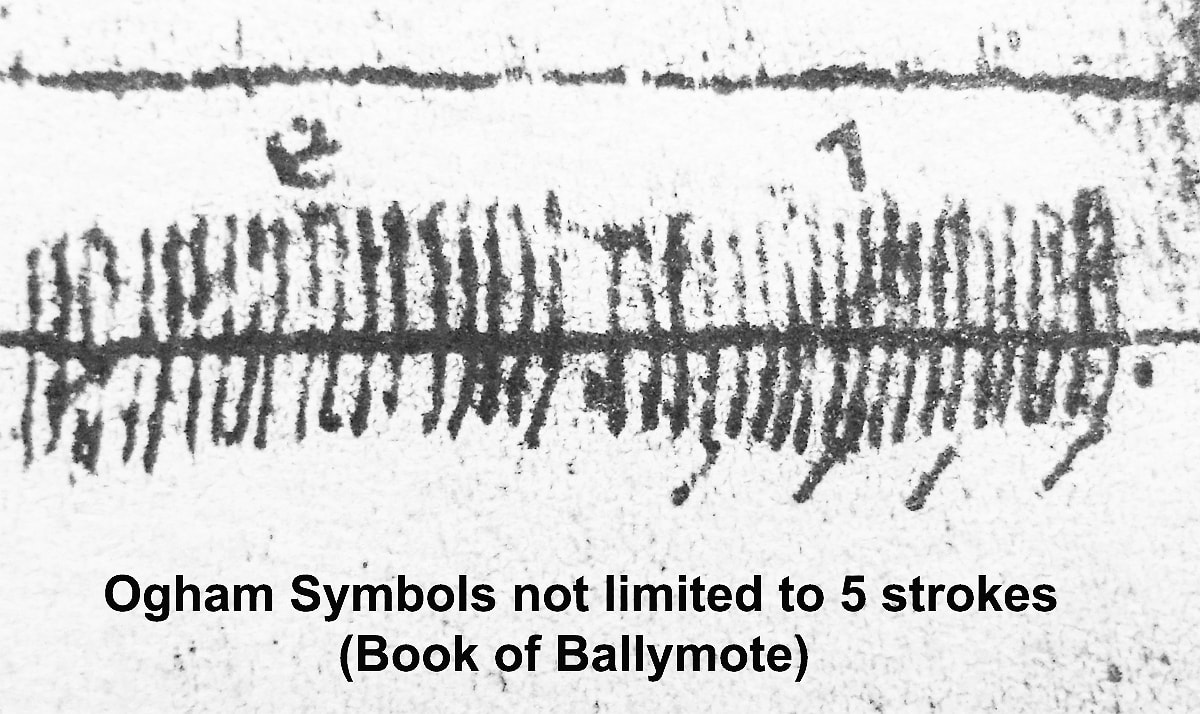

It is possible that parts of this incredible first Ogham message were not recorded, such as the method of delivery which may have been an important factor in understanding these early Ogham exchanges? Was the stick handed over upside-down (feet in the air) for example? Was it laid on the ground pointing away, or placed to the east or west of Lug’s feet? Or, was it passed from a right hand to a left hand, or from a left hand to a right hand? ..and so on. Each of these options could be the key to a full and complete interpretation. But by the recording of Ogma as the writer of the “seven b's on a birch stick”, we have the Church scribes inadvertently linking the first known use of Ogham to the late Bronze Age in Ireland. Many people will say that only 5 strokes were used in Ogham writing but as evidenced in the Plate below - there were many variations in Church Ogham...

It is possible that parts of this incredible first Ogham message were not recorded, such as the method of delivery which may have been an important factor in understanding these early Ogham exchanges? Was the stick handed over upside-down (feet in the air) for example? Was it laid on the ground pointing away, or placed to the east or west of Lug’s feet? Or, was it passed from a right hand to a left hand, or from a left hand to a right hand? ..and so on. Each of these options could be the key to a full and complete interpretation. But by the recording of Ogma as the writer of the “seven b's on a birch stick”, we have the Church scribes inadvertently linking the first known use of Ogham to the late Bronze Age in Ireland. Many people will say that only 5 strokes were used in Ogham writing but as evidenced in the Plate below - there were many variations in Church Ogham...

Plate 2: Multiple strokes for Ogham Symbols

We are also told in Lebor Ogaim that the training of the Gaelic Fili (poets) involved learning one hundred and fifty varieties of Ogham. These high numbers may indicate many different schools with their own variations or dialects that were used to send messages, to keep lists, to keep track of business transactions or numerical tallies of possessions, as well as using Ogham for magical purposes. Written references describe Ogham being originally carved on wood and not on stone; with one exception from the epic ‘Táin Bó Cúailnge’ (The Cattle Raid of Cooley) in which a standing stone has a ring of Iron around it with an Ogham inscription declaring a ‘geis’ taboo that no warrior bearing arms may approach without being challenged to single combat. We are told that Cú Chulainn responds to this challenge by throwing the standing stone with its Ogham inscribed ring of Iron into a lake. Cú Chulainn did have ‘geis’ that he respected but with the high cost of Iron during his era it is unlikely that anyone would use Iron in such a manner on a standing stone. It is hard to believe that any single man could pick up and throw a standing stone into a lake because every standing stone would have a portion embedded in the earth and it is doubtful that anyone would throw a precious ring of Iron away either, so it probably did not happen even though the Church wrote it down. Bear in mind that this is a Church story and all indigenous heroes had to be presented as ‘bad’ and that Iron had a very high weapons value and that just because it was written down (imperial literary tradition) it does not mean it is true.

In ‘Baile in Scáil’ (The Phantom’s Frenzy) we have another church story in which the High King (Conn of the Hundred Battles) is visited by the god Lugh (Lugh had passed over by about 1000 years or more, so this is necromancy - manifesting the spirits of the dead for purposes of magically revealing the future or influencing the course of events!). Lugh recites a poem telling the names and deeds of all the future Kings of Ireland, from Conn himself to the end of time. Lugh’s poem is so long that Conn's Druids write it down in Ogham on four rods of yew wood.

These four rods are eight-sided and twenty-four feet long. That was a very long poem to be carved into 768 foot (234m) of Yew which has an unpredictable grain pattern. Was such a thing even possible? At just 4 Ogham symbols per foot this is over 3072 Ogham symbols long. How many king names were recorded? Yew is a tough, flexible, toxic wood with lots of little pin knots in it that make it difficult to carve straight lines such as 3,000+ Ogham symbols. It is simply not believable that 768 foot (234m) of Yew was craved with Ogham symbols, just like the necromancy of Lugh being brought to ‘life’ to tell Conn about a king list... But if such a poem was recorded on Yew wood in Ogham it implies many interesting things - that this Ogham poem of a ‘future king list’ was intended to be kept somewhere safe, that Druids were used to recording long poems and essays in Ogham on wood and that because Conn died in 157CE at Tara and is buried at Tara we see a continuity of use of Ogham from the Bronze Age into the Iron Age! This implies that the Druids of the Tuatha De Dannan used Ogham (because Ogma invented it) and that Ogham was still in use by the Druids of the Iron Age in 157CE!

In the Táin Bó Cúailnge (another church story): Queen Meave’s army found a tree with carved Ogham symbols on it at a ford or crossing-place on the river. The story tells us that the Ogham symbols carved on the tree were a spell declaring that no one could cross the ford unless they could carve a hobble with one hand. A hobble is part of the leg-cuffs which, when put on a horse would stop it from moving or escaping. So, true to heroic form,

Cú Chulainn carved a hobble with one hand and the Queen’s army simply moved on looking for another ford to cross the river again further along. At the second ford Cú Chulainn cut off a tree branch and wrote in Ogham on it saying that no Connacht (West of Ireland) man could cross over the river unless he could cut off a branch from the tree with one stroke of his sword. At the third ford the Queen’s army found an Oak with Ogham symbols saying that only those who could jump the Oak in their chariots could cross the ford. Many died trying, but the great champion Ferdia achieved it and then fought that fateful battle with his old friend Cú Chulainn. After three days of combat, Ferdia died but so did Cú Chulainn shortly afterwards. A ‘spell’ at a crossing place of a river? It makes no sense to ‘carve’ a hobble because a hobble is a double leg cuff usually made from rope or leather. A sharp sword properly used can cut a branch in one stroke from a tree - so what is that about? Why would an army on its way to war ‘jump the Oak in their chariots’ to then cross the ford? How could anyone jump an Oak tree in a horse drawn chariot anyway? How many died trying? Not credible as history - its more like Hollywood fantasy...

It is not unreasonable to assume that there may have been hand-signing in Ogham too and if Ogham carved on various wood(s) or other materials were handed to another person in a particular order, then very precise messages could be securely and secretly passed on according to the material used, the symbols carved and the method of delivery. This is an implied part of the description of Ogham as the secret language of the Druids. Keep in mind that Ogma’s intention was to “keep learned men apart from rustics”. We only have hearsay evidence from the Church that Lugh dictated a king list for Conn that was recorded in Ogham, that Cú Chulainn wrote geis / spells on trees, threw a standing stone with an Iron band inscribed with Ogham into the river, that Cú Chulainn’s Ogham caused many to die while trying to jump an Oak in their chariots... Hearsay has little value in any court. With over 150 versions of Ogham it has to be mentioned that there could have been substantial differences between the Ogham of the Connaught men to the Ogham of the east coast where Cú Chulainn lived.

In ‘Baile in Scáil’ (The Phantom’s Frenzy) we have another church story in which the High King (Conn of the Hundred Battles) is visited by the god Lugh (Lugh had passed over by about 1000 years or more, so this is necromancy - manifesting the spirits of the dead for purposes of magically revealing the future or influencing the course of events!). Lugh recites a poem telling the names and deeds of all the future Kings of Ireland, from Conn himself to the end of time. Lugh’s poem is so long that Conn's Druids write it down in Ogham on four rods of yew wood.

These four rods are eight-sided and twenty-four feet long. That was a very long poem to be carved into 768 foot (234m) of Yew which has an unpredictable grain pattern. Was such a thing even possible? At just 4 Ogham symbols per foot this is over 3072 Ogham symbols long. How many king names were recorded? Yew is a tough, flexible, toxic wood with lots of little pin knots in it that make it difficult to carve straight lines such as 3,000+ Ogham symbols. It is simply not believable that 768 foot (234m) of Yew was craved with Ogham symbols, just like the necromancy of Lugh being brought to ‘life’ to tell Conn about a king list... But if such a poem was recorded on Yew wood in Ogham it implies many interesting things - that this Ogham poem of a ‘future king list’ was intended to be kept somewhere safe, that Druids were used to recording long poems and essays in Ogham on wood and that because Conn died in 157CE at Tara and is buried at Tara we see a continuity of use of Ogham from the Bronze Age into the Iron Age! This implies that the Druids of the Tuatha De Dannan used Ogham (because Ogma invented it) and that Ogham was still in use by the Druids of the Iron Age in 157CE!

In the Táin Bó Cúailnge (another church story): Queen Meave’s army found a tree with carved Ogham symbols on it at a ford or crossing-place on the river. The story tells us that the Ogham symbols carved on the tree were a spell declaring that no one could cross the ford unless they could carve a hobble with one hand. A hobble is part of the leg-cuffs which, when put on a horse would stop it from moving or escaping. So, true to heroic form,

Cú Chulainn carved a hobble with one hand and the Queen’s army simply moved on looking for another ford to cross the river again further along. At the second ford Cú Chulainn cut off a tree branch and wrote in Ogham on it saying that no Connacht (West of Ireland) man could cross over the river unless he could cut off a branch from the tree with one stroke of his sword. At the third ford the Queen’s army found an Oak with Ogham symbols saying that only those who could jump the Oak in their chariots could cross the ford. Many died trying, but the great champion Ferdia achieved it and then fought that fateful battle with his old friend Cú Chulainn. After three days of combat, Ferdia died but so did Cú Chulainn shortly afterwards. A ‘spell’ at a crossing place of a river? It makes no sense to ‘carve’ a hobble because a hobble is a double leg cuff usually made from rope or leather. A sharp sword properly used can cut a branch in one stroke from a tree - so what is that about? Why would an army on its way to war ‘jump the Oak in their chariots’ to then cross the ford? How could anyone jump an Oak tree in a horse drawn chariot anyway? How many died trying? Not credible as history - its more like Hollywood fantasy...

It is not unreasonable to assume that there may have been hand-signing in Ogham too and if Ogham carved on various wood(s) or other materials were handed to another person in a particular order, then very precise messages could be securely and secretly passed on according to the material used, the symbols carved and the method of delivery. This is an implied part of the description of Ogham as the secret language of the Druids. Keep in mind that Ogma’s intention was to “keep learned men apart from rustics”. We only have hearsay evidence from the Church that Lugh dictated a king list for Conn that was recorded in Ogham, that Cú Chulainn wrote geis / spells on trees, threw a standing stone with an Iron band inscribed with Ogham into the river, that Cú Chulainn’s Ogham caused many to die while trying to jump an Oak in their chariots... Hearsay has little value in any court. With over 150 versions of Ogham it has to be mentioned that there could have been substantial differences between the Ogham of the Connaught men to the Ogham of the east coast where Cú Chulainn lived.

Plate 3: Many Ogham scripts